https://www.latimes.com/local/california/la-me-quake-risk-20160415-story.html

Neighborhoods in the San Fernando Valley, Hollywood, and the Westside will feel the biggest impact from Los Angeles’ new law requiring the retrofitting of wood-frame apartment buildings to better withstand a major earthquake, according to a Times data analysis.

City inspectors spent about two years developing a list of 13,500 so-called soft-story buildings that will probably need seismic strengthening. These apartments, which feature flimsy first floors that often serve as parking spaces, became popular after World War II as Los Angeles was spreading north into the Valley and west toward the ocean.

But they’ve also proved to be vulnerable to violent shaking. Buildings collapsed in the 1989 Loma Prieta and the 1994 Northridge earthquakes, including one apartment building where 16 people died.

Los Angeles building officials sifted through tens of thousands of city records and walked block-to-block to identify these structures. Owners of each building have been put on notice, and a number of them have already begun the retrofitting process. The retrofits can cost as much as $130,000, which has sparked concerns from owners and residents feeling the pressure of rising rents and a housing crunch.

Some property owner groups were opposed to the public release of this data, citing concerns that the list isn’t perfect and that further inspection will show some of the buildings might not need retrofitting.

But seismic safety experts said this preliminary list marks a milestone in providing the public with important safety information about where they choose to live.

“This is a critical first step. Fundamentally, you can’t fix the buildings if you don’t know which buildings need to be fixed,” said seismologist Dr. Lucy Jones, who served as Mayor Eric Garcetti‘s earthquake safety advisor in 2014 and helped shepherd the city’s retrofit efforts into law. “I think the process of creating these records is helping the city come to grips with what is necessary to really do this.”

Renter rights advocates also supported making the list of buildings public.

“Tenants should know, if they’re renting an apartment, how safe those apartments are,” said Larry Gross, executive director of the Coalition for Economic Survival.

Three decades ago, Los Angeles similarly required retrofitting of 8,000 un-reinforced brick buildings that were at risk of collapsing in a major earthquake. Those addresses were also made public, sparking outcry from many property owners. Today, almost all the buildings have been strengthened or demolished. No one died from brick-building damage in the Northridge quake.

These brick buildings populate the more historic parts of the city, including downtown, and were a common form of construction through the early 1930s. Soft-story apartments became popular in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s — and are found in areas that experienced rapid development during that era.

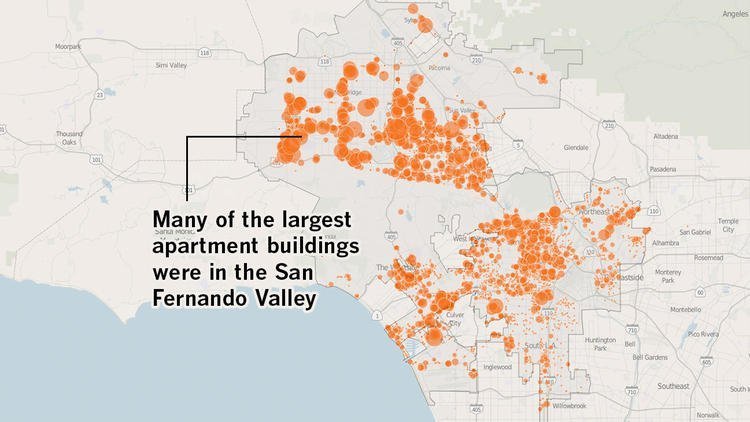

In the Northridge area today, soft-story buildings still make up a significant part of the residential landscape. More than 3,200 buildings on the list — home to at least 75,000 units — are in the San Fernando Valley, according to The Times analysis of the list obtained through a California Public Records Act request.

The analysis identified at least 55 large buildings with 100 or more units. More than half of those are in the Valley, west of the 405 Freeway.

Many soft-story buildings are also in Hollywood, around Koreatown and in certain Westside neighborhoods such as Palms, Mar Vista, West L.A. and Venice. All told, more than half of the 13,500 buildings were in the Valley or the Westside, according to the analysis.

On six blocks of Mentone Avenue in Palms, for example, there are more than 90 addresses listed in the city’s inventory. Similar patterns emerged in other residential clusters nearby.

“I drove down Palms Boulevard, and I was just blown away,” Jones said. “It’s just apartment after apartment after apartment.”

The soft-story design was praised as an affordable and efficient way of providing parking and multiple housing units on a relatively small lot, said Alan Hess, an architect and historian who specializes in California modern architecture.

Accommodating a population boom and the blossoming car-centric culture, these buildings sprang up both in undeveloped spaces in the city and more suburban areas.

“They were definitely meant to be mass housing with a lot of the amenities that people expected in the 1950s and 1960s coming from California. There are decks, there are balconies, there are accessibility to the automobile — parking their car right under their unit basically,” Hess said. “In that sense, they were well-designed for the purpose. They met the need and they were extremely popular both with renters as well as with builders, who could build them pretty easily and cheaply.”

Also known as “dingbats,” these buildings were considered modern and are an iconic snapshot of a very particular time in Los Angeles, Hess said. Many today are beloved for their charming retro feel. The design phased out in the 1970s and ’80s — replaced by taller multi-unit buildings that provided even more housing on a smaller piece of land.

“It wasn’t an awareness of its seismic vulnerability that stopped the expansion of dingbats. It was more to do with the price of land,” Hess said. “You see patterns, especially in places like Palms. You go down the street, and there will be these small bungalows, individual houses from the ’20s, and then next to it would be a row of dingbats, and obviously, a bungalow was torn down for the dingbat. And you go a little bit further, and then you’ll see, from the ’70s or ’80s, a multi-story apartment house on several pieces of property where a couple of dingbats were obviously torn down to build these higher, denser housing units. You see the whole pattern, the evolution of the apartment in Los Angeles.”

Retrofitting the soft-story buildings is important not just for safety reasons, seismic experts said. The apartments represent an important part of L.A.’s affording housing stock, and losing them after a quake would be devastating for a city trying to recover. Jones noted that the Northridge quake alone damaged about 49,000 apartment units, two-thirds of which were in soft-story buildings.

Last month, building owners received courtesy notices outlining the new retrofit law: Beginning in May, the official order to comply will be mailed on a rolling basis. Owners of the city’s largest apartment buildings, with 16 or more units, will receive the first wave of orders. The next wave will include soft-story buildings that have three or more floors, followed by any remaining buildings on the list.

Owners have two years, from the date they receive the compliance order, to either submit proof that the building doesn’t need retrofitting or plans for retrofit or demolition. Within 3.5 years of receiving the order, owners must obtain their retrofit permits.

The entire retrofit must be completed within seven years of receiving the order, officials said.

With the law now in motion, property owner groups have been hosting workshops to help owners navigate the retrofit process. Structural engineers have been putting together webinars and FAQs, and the city hosted a “seismic retrofit resource fair” last week to answer questions about contractors and financing.

The question of how to fund these costly retrofits remains a major concern, said Jim Clarke, who represents the property owner group Apartment Assn. of Greater Los Angeles.

The law requires owners to front the retrofit costs, which can range from $60,000 to $130,000 — possibly even more for larger buildings. The city recently agreed to allow owners to pass on half the costs to tenants through a rent increase of up to $38 more per month.

Lawmakers are also looking into other financial aid options — such as tax breaks and repaying a loan through property taxes.

Clarke called on lawmakers to aggressively continue efforts to secure financial aid, which is crucial to getting these 13,500 buildings retrofitted. Many of the owners are older “mom and pop” landlords who invested their retirement in one building, live in one of the units, rely on the rent as income and cannot easily afford a costly retrofit, he said.

The passage of the law and the release of the list are just the beginning, Clarke said. “It’s not over, people. We need to focus on completing this task, and part of it is finding ways to pay for these projects.”

https://graphics.latimes.com/soft-story-apartments-needing-retrofit/